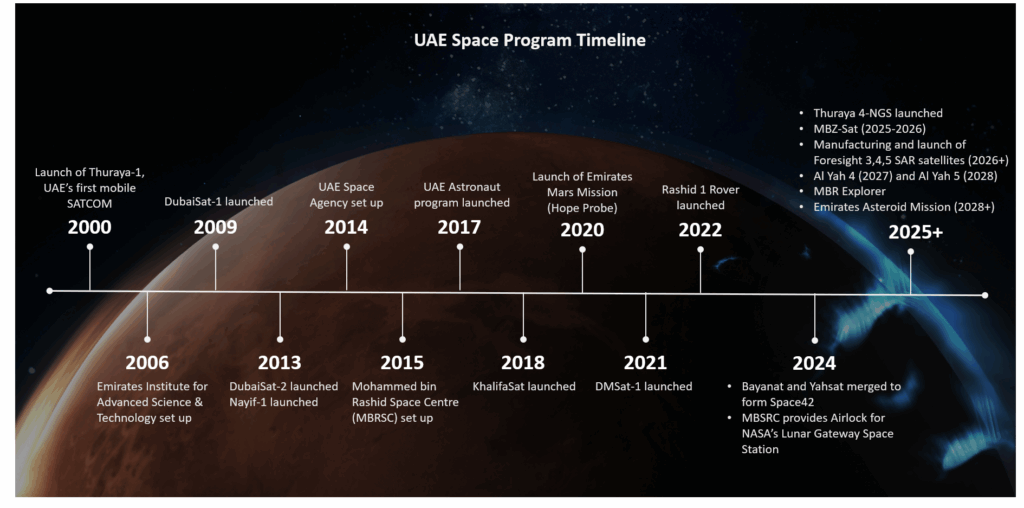

From Thuraya to Hope: Two Decades of Milestones

In a quarter century, the UAE has raced from newcomer to serious spacefaring nation. The story begins in 2000 with Thuraya-1, giving the Gulf its own mobile satcom. Abu Dhabi followed with Yahsat in 2007, launching broadband and broadcast satellites by 2011–12. Meanwhile, Dubai seeded homegrown engineering at Emirates Institution for Advanced Science and Technology (EIAST), producing DubaiSat-1 (2009) and DubaiSat-2 (2013) with help from South Korean partners — stepping stones to space sector independence. By 2014 a federal Space Agency stitched these strands into a national strategy; Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre (MBRSC) took the baton, and in 2018 KhalifaSat—designed and built by Emiratis — reached orbit. In 2019, Hazzaa Al-Mansoori flew to the International Space Station (ISS), turning aspiration into human spaceflight. Then came the leap: the Hope probe, launched in 2020, slid into Mars orbit in 2021, placing the UAE among the few nations to reach the Red Planet on a first attempt. From there the ecosystem consolidated: in 2024, Bayanat and Yahsat merged to form Space42 — fusing satellite communications with geospatial analytics and AI, and creating a single champion to scale downstream services.

This acceleration follows a clear playbook: pair tech with capacity, link public and private actors, and use space to diversify the economy. From Thuraya to Hope to Space42, the arc is simple: access, capability, ambition — then turn space from symbol into system.

An Integrated Model Compared to Other Spacefarers

The UAE’s method of building its space sector differs in important ways from the traditional paths taken by earlier spacefaring nations. Unlike the United States and Russia – whose programs grew from Cold War-era government behemoths – the UAE has from the start treated space as an ecosystem of interconnected players: government agencies, private companies, academia, and international partners. The result is a model that emphasizes public-private partnership and commercial viability alongside national capability. For example, rather than NASA-style in-house development, the UAE often co-develops projects with foreign institutions (University of Colorado helped design the Hope probe; Japanese and European vendors have built UAE satellites) to speed up technology transfer and capability building. But each partnership is structured to train Emiratis and eventually localize production.

More vertical integration is now becoming evident with the UAE piggybacking on existing expertise through contracts and joint ventures. Space42 is a case in point: formed by merging the satellite operator Yahsat and AI firm Bayanat, Space42 has combined under one roof what in other countries might be spread across multiple entities, from satellite manufacturing to geospatial analytics. This integrated approach contrasts with, say, Europe’s space sector, where commercial operators, data analytics firms, and satellite manufacturers are often separate (albeit coordinated via European Space Agency).

Another distinguishing feature is the UAE’s conscious intertwining of sovereign capability and commercialization. Countries like China and India have built sovereign space programs with impressive launch and satellite capacities yet historically kept tight government control over operations. The UAE, by contrast, injects a commercial mindset even into flagship national projects. Space42, for example, is run as a business (listed on the Abu Dhabi stock exchange) that generates revenue by offering services globally – be it selling satellite broadband to Africa or Earth-imagery analytics to Southeast Asia. This means the space sector is expected to pay economic dividends, not just absorb state funds for prestige. It aligns with the UAE’s broader economic strategy: use government investment to kick-start new industries, then spin them into the private sector to drive growth.

We see this in how the UAE Space Agency is promoting a national space industry: through initiatives like a Space Investment Promotion Plan and startup incubators, the Agency aims to make the UAE a regional hub for commercial space activity. In effect, the UAE is pursuing a hybrid of the American approach (nurturing a thriving private space economy) and the self-reliance of older programs (insisting on domestic ownership of critical assets). Launch capability remains a gap – the UAE still relies on foreign rockets to send its satellites up – but given the ready availability of commercial launch services worldwide, the UAE has sensibly focused instead on satellites, applications, and downstream services where it can differentiate. In time, if small launchers become economically viable, one can imagine the UAE investing in those too (perhaps in partnership with foreign firms). For now, it has managed to become a spacefaring nation without the huge expense of developing its own rockets or spaceport.

Internationally, the UAE’s approach has won it a reputation as a collaborative and agile player in space. It actively works with established agencies (over 30 agreements signed, including with NASA, CNES, JAXA, etc.) and even spearheaded an Arab Space Cooperation Group to pool regional talents. This stands in contrast to the competitive posturing of traditional space races. The UAE model suggests that for newer entrants, cooperation can accelerate capability faster than competition. It also shows how a space program can be built with a clear eye on economic and societal benefits from the start – something legacy programs only pivoted to after decades of purely scientific or military pursuits. Overall, the UAE’s integrated model may serve as a blueprint for other emerging space nations: leverage global partnerships to gain technology, invest in local talent and infrastructure, integrate efforts under strategic public-private entities, and always link space projects to tangible economic value and national pride.

Fusing AI Innovation with Space Capabilities

Another defining feature of the UAE’s approach is its fusion of artificial intelligence (AI) and space technologies to create smarter, more useful space systems. Rather than treating satellites as mere hardware in orbit, the UAE is building an AI-powered ecosystem to fully exploit space data. A prime example is the Geospatial Intelligence Hub (gIQ) – a cutting-edge analytics platform developed jointly by UAE engineers and the Space Agency. Housed under Space42, gIQ uses AI and machine learning to turn raw satellite imagery and sensor inputs into actionable insights in real time. During heavy rainstorms in 2024, for instance, the platform ingested radar satellite data and digital twin models to deliver instant flood detection and damage maps, enabling emergency responders to target relief where it was needed most. From monitoring illegal fishing and oil spills to planning smart cities, these AI-driven geospatial tools are multiplying the impact of the UAE’s space assets across civilian and defense domains.

Crucially, the UAE is investing in next-generation satellites that themselves embody AI and advanced sensing. In 2024, launched the UAE’s first synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellite, Foresight-1, which can see the Earth’s surface day-or-night and through clouds. This marked the start of an indigenous SAR constellation providing high-resolution imaging for everything from disaster management to crop monitoring. To accelerate this capability, Space42 entered a joint venture with Finland’s ICEYE to manufacture SAR satellites in the UAE, localizing production of these sophisticated spacecraft. The venture not only delivers technology transfer into Emirati hands but also builds a domestic supply chain for space components – aligning with the country’s push for self-reliance. In parallel, the UAE’s defense technology conglomerate, EDGE Group, launched a dedicated space division called FADA to develop sovereign satellite platforms, including SAR and optical payloads, with an emphasis on national security applications. EDGE’s FADA has been selected as prime contractor for the UAE Space Agency’s new Sirb program, which will orbit a trio of SAR satellites by 2026–2028. Through FADA, the UAE is standing up assembly, integration and testing facilities to build satellites at home, echoing its broader strategy of vertical integration in the space sector.

Equally notable are the UAE’s partnerships with global tech players to infuse its space efforts with the latest digital innovations. A striking example is the UAE Space Agency’s alliance with Amazon Web Services (AWS). In 2022 the Agency became the first in the Middle East to sign a strategic accord with AWS, aiming to leverage cloud infrastructure and AI services for space initiatives. AWS is providing UAE start-ups and researchers with cloud credits, training, and open data platforms to catalyze new space applications – even the Hope Mars probe’s science data is being hosted and analyzed on AWS cloud servers¹. Additionally, local AI champions like G42 (the Abu Dhabi-based AI firm behind Space42) are deeply involved in space-data analytics and satellite operations. The gIQ platform mentioned earlier is essentially a G42/Bayanat creation in partnership with the Space Agency, illustrating how domestic AI talent is being marshalled for space. By marrying AI, big data, and space in this way, the UAE not only maximizes the practical returns of its satellites but also positions itself at the forefront of what the global industry sees as the next big leap – intelligent Earth observation and autonomous spacecraft operations. It’s a symbiotic relationship: AI makes UAE satellites far more powerful in application, while the space program provides a grand challenge to drive the UAE’s AI sector to world-class levels.

Building a system that delivers

The message is clear: beyond Mars headlines and astronaut selfies, the strategy is to turn prestige into productivity — high-skill jobs, home-grown industry, and inbound investment. The results are tangible: more than fifty space-related entities and thousands of roles where there were almost none before 2000; a growing market for downstream services — precision agriculture, urban planning, and other satellite-data applications—now used by government and business, creating new revenue lines. The talent pipeline is widening too, with rising STEM enrolment and the first national PhD in space science launched after Hope.

What sets this model apart is the blend of AI-driven analytics, sovereign data and infrastructure, and public–private commercialization under a long-horizon mandate. Risks remain — technical, financial, geopolitical—but they’re best managed through the same patient institution-building and international partnerships that got the program here. In sum: flagship missions to inspire, institutions to scale, markets to monetize. The program has moved from symbol to system — and, if execution stays disciplined, from momentum to durable advantage.

Arjun Sreekumar is an Associate Director at KPMG, where he leads the Aerospace, Defense & Space portfolio within the Strategy & Operations vertical for the Lower Gulf. A well-recognized voice in the aerospace, defense, and space industry, he brings extensive experience advising governments, national champions, and global primes across Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

He has led the design of national offset and localization strategies, overseen commercial and technical due diligence for next-generation platforms, and directed industrial transformation programs across the defense and space sectors. Arjun’s work has shaped sovereign capability roadmaps, dual-use innovation strategies, and export enablement frameworks that are helping define the region’s industrial future.

You can find more interviews and articles on the UAE space ecosystem in our latest magazine.