When we envision the future of the “cloud,” we often picture gleaming white server racks in a temperature-controlled room in Virginia or Dublin. In recent years, a more ambitious vision has emerged: the orbital data center. Proponents speak of a “green” frontier where servers are powered by 24/7 solar energy and cooled by the infinite void of space.

However, as we move from science fiction to the hard engineering of 2026, the reality is setting in. The idea of a “one-to-one” terrestrial data center replica (i.e., a monolithic warehouse floating in orbit) is likely a physical impossibility. If we are to move computing into the stars, we must stop trying to export Earth-bound architecture and start designing for the vacuum.

The Thermodynamics of Orbit: Why the Monolithic Space Data Center is a Physical Fallacy

The narrative surrounding “orbital cloud computing” has matured rapidly in the past year or so. As terrestrial data centers face increasing scrutiny over land use, water consumption for cooling, and carbon footprints, the vacuum of space is often presented as the ultimate “green” frontier. The pitch is simple: unlimited solar energy and an infinite heatsink. However, when we apply rigorous engineering principles to this vision, the “one-to-one” Earth-equivalent data center, a centralized, multi-megawatt facility in orbit, reveals itself to be a thermodynamic and logistical impossibility.

To build a functional digital infrastructure in space, we must move away from the “warehouse” model and toward a decentralized, space-native architecture. This transition requires overcoming the brutal reality of orbital physics through distributed edge computing and radical advancements in semiconductor materials.

The Radiative Cooling Bottleneck

The primary hurdle for any orbital data center isn’t launch cost or orbital mechanics; it is the fundamental law of thermodynamics. On Earth, data centers are cooled via convection. We move massive volumes of air or water over heat sinks, carrying thermal energy away from the silicon. In the vacuum of space, convection does not exist. The only mechanism for heat rejection is thermal radiation.

The efficiency of this process is governed by the Stefan-Boltzmann law, which states that the power radiated from a black body is proportional to the fourth power of its absolute temperature.

For standard terrestrial hardware, which typically operates within a narrow thermal envelope 20-35°C, the radiative efficiency is remarkably low. To reject the heat generated by a 10MW server farm at these temperatures, the required radiator surface area would be measured in square kilometres. This creates a massive structural paradox: the cooler you want your servers to run, the more gargantuan your cooling infrastructure must become. Unlike Earth, where the atmosphere acts as a passive heat sponge, space demands an active, massive, and incredibly fragile radiator geometry for every kilowatt of heat generated.

The Scale Paradox: Surface Area, Power, and Debris

To power a multi-megawatt facility, you need solar arrays of equivalent scale. When you combine the surface area required for power generation with the area required for thermal radiation, you create a spacecraft with a colossal cross-section. This leads to three critical failure points:

- Orbital Debris Flux: A structure with a cross-section of several square kilometres has a statistical certainty of being struck by Micrometeoroids and Orbital Debris (MMOD). In Low Earth Orbit (LEO), where debris density is highest, maintaining a monolithic structure becomes a game of Russian Roulette. A single puncture in a pressurized cooling loop could lead to a catastrophic “thermal runaway” event.

- Station-Keeping and Drag: Even in LEO, there is a trace atmosphere. A giant radiator array acts as a massive sail, creating atmospheric drag that requires constant, fuel-heavy station-keeping manoeuvres to prevent orbital decay.

- The Maintenance Gap: Modern IT infrastructure relies on the “hot-swap” philosophy. On Earth, a failed power supply or a cracked fibre line is a 15-minute fix for a technician. In orbit, the cost of an Extravehicular Activity (EVA) or a robotic servicing mission is orders of magnitude higher than the value of the hardware being repaired. A monolithic data center is a “single point of failure” on a planetary scale.

The Distributed Solution: Optical Inter-Satellite Links (OISL)

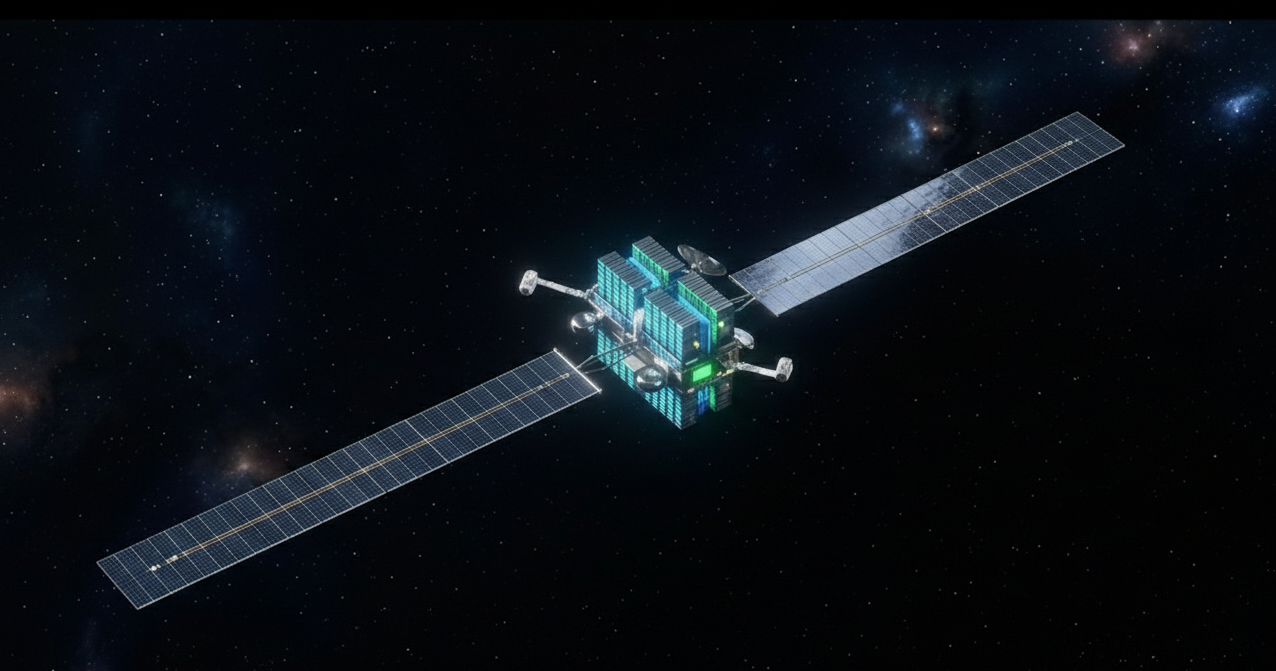

If the monolithic warehouse is a dead end, the future lies in a distributed orbital mesh. Instead of one giant facility, we should envision thousands of small, specialized nodes interconnected through a high-speed backbone.

The “glue” that makes this possible is the advancement in Optical Inter-Satellite Links (OISL). Using lasers instead of traditional Radio Frequency (RF) allows for terabit-per-second data transfer between nodes with minimal latency and zero atmospheric interference. In this architecture:

- Redundancy is Native: If a single node is destroyed by debris or disabled by a solar flare, the network dynamically reroutes data through the mesh, similar to the BGP (Border Gateway Protocol) routing used on the terrestrial internet.

- Coordination Nodes: A subset of these satellites acts as “master nodes,” running container orchestration (similar to Kubernetes) to manage the distribution of compute tasks across the swarm based on the current thermal and power status of each individual node.

Hardware Evolution: Wide-Bandgap Semiconductors

To make this distributed model energetically feasible, we must move away from consumer-grade silicon. The thermal problem is significantly mitigated if we allow the hardware to operate at higher temperatures.

This is where Wide-Bandgap (WBG) semiconductors, such as Gallium Nitride (GaN) and Silicon Carbide (SiC), become essential. Unlike traditional silicon, which begins to suffer from carrier leakage and structural degradation above 100°C, GaN and SiC can operate reliably at temperatures exceeding 200°C.

Recalling the T4 relationship in the Stefan-Boltzmann law, doubling the operating temperature doesn’t just double the cooling efficiency, it increases it by a factor of 16. By developing “Space-Native” processors that thrive in high-heat environments, we can reduce the required radiator area by over 90%, allowing high-performance computing to fit within a standard SmallSat or CubeSat form factor.

Furthermore, another option is to integrate Neuromorphic Computing. These chips process information using “spikes” of energy, mimicking the human brain’s efficiency. By only consuming power when an event occurs, these processors minimize the “idle heat” that plagues traditional CPUs, making them perfect for the strict power budgets of orbital nodes.

The True Value: Orbital Edge Computing

Why go through this trouble? The goal isn’t to host a website in space. It’s to solve the “Data Gravity” problem.

Earth-observation (EO) satellites currently generate petabytes of raw data. The bottleneck is the “Downlink Gap.” Satellites collect data at gigabit speeds but can only transmit it back to Earth when they are over a ground station. This results in “stale” data.

A distributed orbital data center provides Orbital Edge Computing (OEC). By processing raw hyperspectral imagery or Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) data locally within the mesh, the system can discard the 99% of data that is redundant (like images of clouds) and only transmit the high-value insights. This transforms the satellite from a simple “camera in the sky” into an autonomous intelligence agent. Instead of sending down a 10GB image of a forest, the satellite processes the data locally and sends a 10KB alert: “Wildfire detected at these coordinates.” By processing data at the source, we bypass the bottleneck of the “ground-to-space” link and unlock real-time intelligence for everything from climate monitoring to autonomous space traffic control.

The dream of a “one-to-one” Earth-equivalent data center in space is a relic of 20th-century thinking. To conquer the orbital frontier, we must embrace the constraints of the vacuum. By moving toward a distributed mesh of high-temperature, low-power nodes connected by laser links, we create an infrastructure that is resilient, scalable, and, most importantly, physically feasible. The future of the cloud isn’t a floating warehouse; it is a smart, hot, and highly distributed web of light and information.

Iulian Emil Juhasz is an aerospace engineer and space entrepreneur with more than 14 years of experience in leading teams and projects and working with various customers from governmental agencies to large space system integrators. Mentor in the European Innovation Council Scaling Club, Italian TakeOff Accelerator, ESA BIC Czech Republic and NATO DIANA.