In this article, Kevin M. O’Connell, Senior Expert at AzurX contributing to strategic initiatives on space commerce and policy between the U.S. and the Middle East, highlights how Gulf nations, especially the UAE and Saudi Arabia are accelerating space investments for prestige, economic diversification, and strategic autonomy. Fueled by public visions and private capital, regional capabilities, partnerships, and commercial ventures are expanding. As global space competition grows, the Gulf is emerging as an active space economy player, attracting investment, technology, and international cooperation.

The new year brings great expectations for the global space economy. As geopolitical relationships shift, there is universal interest in leveraging space for social, economic, and national security interest. [1] Most often heard these days in capitals from Ottawa to Berlin to Tokyo is the need to develop “sovereign” space capabilities which drives unprecedented levels of investment and a focus on how to move quickly.

The Gulf and the broader Middle East are no exception. While far from being a recent interest – the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia have had ambitious and successful programs over the past two decades – space represents a unique source of national prestige, economic diversification, and strategic autonomy.

Historically known for their oil-based economies, many Gulf nations are channeling resources toward the development of advanced technologies and knowledge-based economies as the basis for diversification. Across the region, space is increasingly seen as an area for long-term focus and investment as laid out in the UAE’s Vision 2071 and advanced through near-term priorities under ‘We the UAE 2031’, Oman’s Vision 2040, and Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. These and other strategy documents reflect an emphasis on the basic elements required to develop the local space economy – public and private investment, entrepreneurship and talent, predictable regulatory environments – as well as the growing importance of leveraging commercial capabilities.

How does this align with other global trends? First, almost 80% of the estimated $613B global space economy is conducted by commercial organizations. [2] The ability to create space capabilities increasingly depends on leveraging private firms with the ability to harness trillions of dollars in adjacent commercial investment (cloud computing, analytics, visualization) while looking to incorporate new space-related technologies (artificial intelligence, autonomy, quantum computing, and robotics) as a source of comparative advantage. Commercial firms also do a better job of anticipating future needs and opportunities than traditional government-driven requirements systems. Traditional Gulf-region companies like Arabsat, Gulfsat, and Space42 now occupy a rapidly growing regional and increasingly global marketplace. Alongside them, emerging companies like AzurX, Orbitworks, Leap 71, SARsatX, Oman Lens, and Madari Space are making breakthroughs across commercial space segments.

Second is the rapidly growing importance of private capital. While national government investments are important for sovereign needs, private capital serves as an accelerator of innovation, as it seeks differentiation among ideas, business acumen in entrepreneurs, and looks at risk differently than government. As we enter 2026, we have seen the largest recorded investments ($5B across 115 companies in Q3/2025) [3] in the space sector since early in the decade, fueled by clearer government signals about the growing importance of space, improved investor familiarity with the space sector, and an increase in merger and IPO activity. Further, the Trump Administration, in its recent Executive Order on space, signaled its intent to attract at least $50B in additional private investments by 2028 [4]. While data about private space investment in the Gulf is scarce, the UAE’s recent $12B investment is designed to support the growing demand for increased communications and observation data as well as to attract private capital interested in frontier technologies. [5]

Third, as economics finally plays a role in how we think about space (as opposed to pure techno-optimism or military thinking), countries need to focus on the roles they are best suited for, based on their academic and talent base and their industrial strengths. Being excited about space is natural but will only get countries so far; making progress in the space economy requires a hard-hitting focus on what one must do and what it does best. While the UAE has the most extensive experience in space – including deep space exploration, human spaceflight, satellite imagery, and communications – Saudi Arabia hopes to highlight the value of space data (in NEOM, for example) for autonomous mobility, resource management, renewable energy and to serve as a hub for mitigating the effects of space debris; Oman hopes to leverage its unique geographic position and its planned Etlaq launch site to serve the space transportation needs of the Gulf, the broader Middle East, and even the African continent (itself with a rapidly growing interest in space). Gulf countries are already thinking about the cost-competitive and trade aspects of space by hosting capabilities within special economic zones.

“Almost 80% of the estimated $613B global space economy is conducted by commercial organizations.”

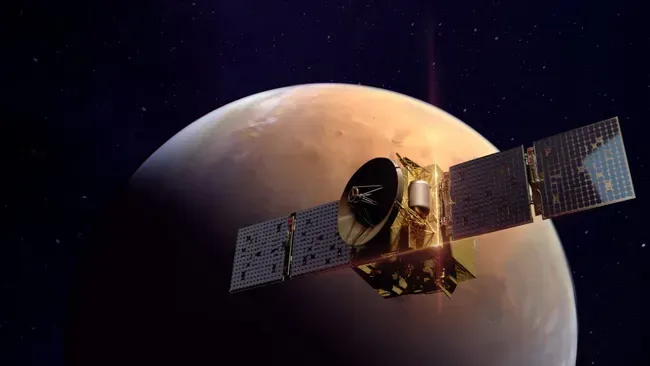

Plans and visions aside, there has been substantial progress. Last year, the UAE launched Etihad-SAT, the first synthetic aperture radar, improving regional space capabilities. The Emirates also launched six communications and observation satellites in early 2025, including Thuraya 4 and MBZ-SAT (the region’s most advanced satellite, delivering high-resolution Earth observation data), and more recently launched PHI-1, a modular satellite involving international payloads. The Rashid Rover-2 is now planned for a historic landing on the Moon’s far side in late 2026. Saudi Arabia advanced its human spaceflight and satellite manufacturing capabilities, signed a private deal for a sovereign communications constellation, and will host a major space debris conference in January 2026. PIF‑owned Neo Space Group expanded satellite services, completed key acquisitions, secured major clients, and won a top award for next‑gen inflight connectivity. While not at the scale of these two Gulf spacefarers, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Oman are rapidly exploring new partnerships and investing in talent and space industry incubators.

Partnerships are critical. The number of regional cooperative space projects is growing, such as the recently launched Arab Satellite 813, a climate and earth observation system designed to develop regional expertise and information sharing; UAE and Kuwait announced they would work together in space science, satellite development, and research. Over the next decade look for even more specialization and investment in an Arab space ecosystem that allows for shared research, infrastructure, and innovation.

Global leadership and international partnership opportunities are growing. The UAE leads the UN COPUOS Expert Group on Space Situational Awareness and hosted last year’s World Space Week. While the Gulf region has a long history of partnership with NASA and the United States, its growing interest in space has the close attention of Moscow and Beijing. The UAE was an original signatory to the Artemis Accords in 2020 and subsequently joined by Saudi Arabia and Bahrain. US-Emirati space cooperation has been extensive, and President Trump’s 2025 regional visit strengthened U.S.-Saudi ties in space, aviation, and advanced technology, building on the mid-2024 cooperation agreement between the two countries.

Yet America’s leadership is facing increased competition: China is active in trying to recruit Gulf country astronauts and seek other sources of influence consistent with the region’s key role in their Belt and Road Initiative, which has a substantial space and geospatial component. [6] Reflecting this trend, Omani and Emirati academic institutions have become participants in the Chinese and Russian International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) program in recent years.

Still missing is the robust commercial cooperation that will fuel the speed and direction of the global space economy. Gulf entrepreneurs, armed with the patient capital of their sovereign wealth funds, have learned how to start small and build up capabilities that still dwarf government space system development. [7] The UAE’s formation of Space42 and the Saudi formation of Neo Space Group are designed to demonstrate end-to-end commercial capabilities while incorporating the newest technologies. Another example: Qatar’s Es’hailSat is expanding beyond communications into the satellite imagery market with a view toward market diversification and overseas expansion.

Notable commercial deals between the Gulf and the United States are the 2024 tag-up between Loft Orbital and the UAE’s Marlan Space (known as Orbitworks), designed for mass satellite manufacturing and leverage of a growing global infrastructure for data collection, processing, and analysis. Last year, US-based iRocket signed a five-year agreement worth $640 million with SpaceBelt KSA for up to thirty orbital launches. The Trump Administration’s intent to promote US business abroad should create many additional opportunities for commercial partnership in the region, although strategic US-China competition in space, and especially to return to the Moon, could invoke complex export control and foreign investment rules that will be uniquely unhelpful. A proactive US policy would include regional agreements on technical assistance, infrastructure, and finance, especially given the region’s rapidly growing financial wealth. [8]

“Being excited about space is natural; building a competitive space economy requires ruthless focus on what a country does best.”

More delicate still is the extent to which the Gulf region’s space pursuits are being driven by military and security needs. History has shown that trying to prevent regional partners from acquiring advanced capabilities is a feckless exercise, often resulting in failure, pursuit of alternative sources, and requiring rapid adaptation. The Trump Administration is likely to look at growing Gulf interest in space as an opportunity to decrease security dependency – as it has explicitly in Europe and with Japan – and as an opportunity to increase American exports and interoperability with American systems. [9] As missile defense plays a greater role in US security strategy, aligning Gulf missile defense systems against Iran and its proxies will become a priority.

The Gulf States and the broader Middle East are no longer passive participants in the global space economy – they are active architects of its future. Their patient investments in technology, talent, and partnerships signal a strong shift with implications for space governance, economics, and global competition. For policymakers, innovators, and investors, this is a region to watch closely as it transitions away from energy dependence to space, its related technologies, and the many new benefits that they will create.

Kevin M. O’Connell is a recognized expert on space commerce, the global space economy, and U.S. national security, with nearly four decades of advancing space commercialization and technological competitiveness. He has served in senior roles across the Departments of Commerce, Defense, State, the National Security Council, and the Office of the Vice President, and led RAND’s Intelligence Policy Center. As Director of the Office of Space Commerce in the first Trump Administration, he facilitated private sector innovation, partnerships, and U.S. competitiveness in space. Kevin also serves as a Senior Expert at AzurX, contributing to strategic initiatives on space commerce and policy between the U.S. and the Middle East.

References

[1] Kevin M. O’Connell and Kelli Kedis Ogborn, “How Countries Can Increase Their Participation in the Global Space Economy,” Space News, October 15, 2024, available at https://spacenews.com/how-countries-can-increase-their-participation-in-the-global-space-economy/ [2] Space Foundation, The Space Report, Q2 2025, as summarized at https://www.spacefoundation.org/2025/07/22/the-space-report-2025-q2/ [3] Space Capital Quarterly: Q3 2025 available at https://www.spacecapital.com/reports/space-investment-quarterly-q3-2025 [4] Donald J. Trump, “Executive Order on Ensuring American Space Superiority,” December 18, 2025, accessed at https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/12/ensuring-american-space-superiority/ [5] Arabian Business https://www.arabianbusiness.com/abnews/uae-space-sector-takes-off-with-12bn-investment-and-private-sector-push [6] Atlantic Council, “Geopolitics in Orbit: What Gulf Moonshots Mean for Washington,” April 25, 2025, accessed at https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/geopolitics-in-orbit-what-gulf-moonshots-mean-for-washington/ [7] Adrienne Harebottle, “Global Influence: The Middle East is Rewriting What It Can Do in Space,” Via Satellite, August 25, 2025, available at https://interactive.satellitetoday.com/via/september-2025/global-influence-the-middle-east-is-rewriting-what-it-can-do-in-space [8] Matthew Montiel, “Countering China’s Space Silk Road: A US Partnership Model for the Middle East” Space News, November 13, 2025. [9] Fact Sheet: President Donald J. Trump Secures $200 Billion in New U.S.-UAE Deals and Accelerates Previously Committed $1.4 Trillion UAE Investment” — The White House (May 15, 2025)Cover image: H.H. Khaled bin Mohamed bin Zayed, H.H. Hamdan bin Mohammed bin Rashid tour Natural History Museum Abu Dhabi in Saadiyat Cultural District (WAM)